So there I am, minding my own business the Sunday before last, when the Internet goes crazy. Or, rather, one of the corners of the Internet that I keep an eye on went crazy.

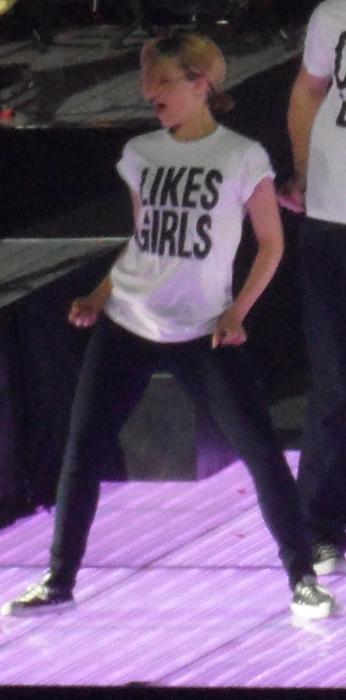

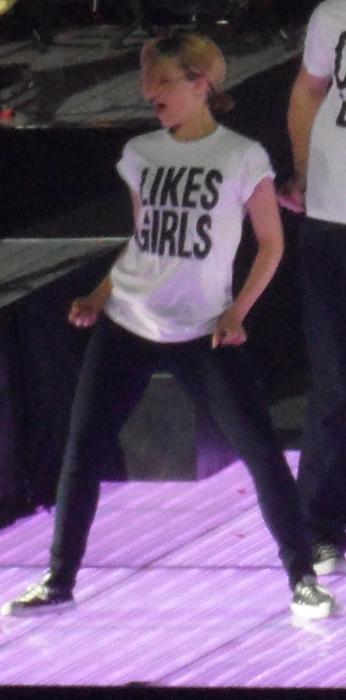

From D. Agron’s Tumblr at http://felldowntherabbithole.tumblr.com/post/6453072763

I’ll admit it: I have a Google alert set for Dianna Agron. It’s what I do these days when I like an actor (which others, I’ll never tell!). So when the actor in question—who’s female and heretofore evidently heterosexual (Achele shippers notwithstanding. Also, check out Urban Dictionary’s Acheleography definition; it’s hilarious!)—wore a “Likes Girls” t-shirt to perform a Glee Live show in Toronto, my inbox became a popular destination—15 news stories in the first 24 hours, then 16 more over the next 3 days (many thanks are due to threaded emails that it didn’t actually fill).

There were questions: Did Glee’s Dianna Agron come out as bisexual with a tshirt? and dry factual headlines: Glee’s Dianna Agron “Likes Girls” T Shirt in Toronto and (not-so) subtle digs at fans: Dianna Agron Wears “Likes Girls” T-Shirt, Gleeks Freak Out.

And there was squee. Oh dear God was there squee. Some of my favorites from the tumblr tag “dianna agron come out riot”:

angelsfallenknight: I AM DYING. JEEEEESUS. CAPS LOCK WON’T GO OFF. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAH! ‘I LIKE GIRLS’ AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!

chikaru: so dianna agron likes womenin other news water is wet, pope is catholic etc

Then, about 12 hours after the first alerts had come through, the tone shifted. The second set of headlines included: Dianna Agron explains ‘likes girls’ t-shirt worn during live show and Dianna Agron Talks About Gay Issues.Basically, these stories said: “Ha ha, just kidding, she doesn’t have the gay. No worries!”

Along with this batch came Agron’s own essay, published at her tumblr, which is what the walking back of the gay speculation was drawing on—as far as I know, she hasn’t given any interviews on it yet. The piece was sort of a “gay pride month is really important because clearly it’s still not that awesome to be gay, so I’m going to stand up for gay rights” statement.

And honestly I still can’t decide how I feel about it. On one hand, it’s like, “Well, that’s easy for you to say. You get to go back to having heterosexual privilege when you take the shirt off.” But on the other hand, she is putting herself on the line in some sense, because she is choosing to stand with (and temporarily as) a category that’s socially devalued. And putting herself—her career, perhaps—“at risk” in that limited sense is certainly better than no sense at all.

But what really stood out to me about her essay was the logic by which she counted herself among those who like girls:

I love my family, my friends, my co-workers…and they all consist of girls AND boys. I do tell them that I love them. Yesterday, during our second show, Instead of wearing my usual shirt during “Born This Way” I decided to wear one that said “Likes Girls”. It should actually have read, “Loves Girls”, because I do. The women in my life give me things that the men in my life can’t. And vice-versa. No, I am not a lesbian, yet if I were, I hope that the people in my life could embrace it whole-heartedly. And let me tell you, I can easily spill (quite comfortably) what I admire, respect and think is beautiful about any of the women in my life. Piece of cake!

Last night, I wanted to do something to show my respect and love for the GLBT community. Support that people could actually see. Which is why I decided to change my shirt for the show.

Reading this, I had a total sense of déjà vu. I’d read this before:

I mean the term lesbian continuum to include a range—through each woman’s life and throughout history—of woman-identified experience, not simply the fact that a woman has had or consciously desired genital sexual experience with another woman. If we expand it to embrace many more forms of primary intensity between and among women, including the sharing of a rich inner life, the bonding against male tyranny, the giving and receiving of practical and political support [ . . .].

The above quote is from Adrienne Rich’s 1980 essay “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” (from the version in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, p.239), and the resemblance is sort of uncanny.

There’s the same move to relate loving and supporting women with having same-sex sex—deliberate and political on Rich’s part, not entirely elaborated on Agron’s.

At the same time, both authors also insist that they aren’t identical. Agron says “I love girls. Just not for fucking.” Rich distinguishes between the above “lesbian continuum” and “lesbian existence,” which she defines as “both the fact of the historical presence of lesbians and our continuing creation of the meaning of that existence”—meaning that this is where we get literal, actual lesbians (p. 239).

Rich, then, would argue that Agron is actually sort of a lesbian, sex-free love of women notwithstanding, since she’s on the lesbian continuum.Indeed, Rich wanted to “consider the possibility that all women [ . . . ] exist on a lesbian continuum,” because this would let us “see ourselves as moving in and out of this continuum, whether we identify ourselves as lesbian or not” (p. 240).

What Rich wanted to do in the essay, as the title suggests, was figure heterosexuality not as a “natural” disposition—either for all women, in which case lesbians are unnatural, or for most women, which makes lesbians natural (whatever that means) but unusual—but something that had to be imposed to make women identify with men’s interests rather than their own (which has its own set of problematic assumptions—I’ll get there).

She questioned “why species survival, the means of impregnation, and emotional/erotic relationships should ever have become so rigidly identified with each other,” contending that, however related they seem to us now, there was nothing inevitable about this outcome (p. 232).

Ultimately, through proposing this continuum, Rich wanted to help women “feel the depth and breadth of woman identification and woman bonding that has run like a continuous though stifled theme through the heterosexual experience,” with the goal being “that this would become increasingly a politically activating impulse, not simply a validation of personal lives” (p. 227).

That is, it isn’t just to get women to come together and identify as or with lesbians for a round of kumbayah, but to further feminist action. That part remains unrealized in Agron’s rendition, and that possibility is a danger Rich herself realized about the term.

Rich wrote an addendum to “Compulsory Heterosexuality” the following year–when it was to be anthologized in Powers of Desire, in order to respond to some queries from the editors of that volume–in which she addressed this issue: “My own problem with the phrase is that it can be, is, used by women who have not yet begun to examine the privileges and solipsisms of heterosexuality, as a safe way to describe their felt connections with women, without having to share in the risks and threats of lesbian existence” (249).

This definitely gets at what makes me uncomfortable about Agron’s statement.She can be edgy and wear a “Likes Girls” shirt as a way to proclaim her love for the women in her life because she has enough privilege–as heterosexual, but also as white, as normatively gendered, as meeting standards of attractiveness, as wealthy, and as a celebrity–to insulate her from what that would entail were she someone else.

Rich wanted to make it “less possible to read, write, or teach from a perspective of unexamined heterocentricity” (p. 228), but 30 years down the line being unexamined is clearly still possible. Certainly, Agron’s post did not succeed at really examining her own positionality, since the larger argument is grounded in a presumption that straight people ought to be nicer to those poor queers.

I’m sure she doesn’t realize it, but this relies on an assumption of heterosexual superiority. They are apparently in a position to tolerate us because we are the lesser objects of tolerance in the equation (see Wendy Brown’s2006 book Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire).

This isn’t to pick on Agron. These are things I think about because it’s my job. These are ways of seeing I am trained in. Her job and her training are something else. She did ok. She really did. For a young person (though, I have to remind myself, not as much younger than me as it feels like) whose fame has led to her opinion—about anything—being news, she’s doing pretty well.

But it is to temper the praise she’s getting for being SO progressive. Seriously, you’re going to ask “Is Dianna Agron more supportive of LGBT rights than the rest of the “Glee” cast?” on account of one blog post? And this blog post? She’s not some kind of new gay patron saint.

I’m also not trying to hold up Rich as the true homosaint. I will be the first to tell you that there are a number of problems with her piece—I was, literally, when we read this in my Queer Theory class a couple years ago. Rich wants to open the arms of lesbian feminism to heterosexual women and express that, though heterosexuals get more privilege, it’s the structure of the system that makes that so and not necessarily heterosexual woman going around acting to oppress, which is great.

But, like many a second-wave feminist, Rich doesn’t get that men aren’t the enemy. They benefit from the unequal distribution of power, sure, but they don’t completely control it. In fact, men can be allies to change things—just like Rich argues that heterosexual women can.

Rich seems to mistake the situation as one in which men are running the system in a smoky room somewhere, trying to trick women into heterosexually identifying with men’s interests rather than their own true female/lesbian continuum interests. This is ridiculous for a number of reasons, not least because women don’t inherently care about the same things.

Indeed, the assumption that all women share interests simply by virtue of their membership in the category demonstrates that at that point Rich did not understand her own race or class privilege all that well—I’ll give her the benefit of the doubt and assume she does now. She makes offhand references to the importance of race and class, but they aren’t a substitute for a thorough and integrated understanding of how gender and sexuality are racialized.

In the end, what’s interesting about both Agron’s essay and Rich’s is that they both want to trouble or push the boundaries of categories but end up reinforcing them instead.

Agron wore a tshirt that was meant (when it was printed) to indicate same-sex attraction to proclaim both her platonic love of the women in her life and her support for those who do have such attractions. That’s a blurring of boundaries that had a great deal of potential to make things queer–but she contains it by making an unequivocal statement that “I am not a lesbian.” Why not refuse the question altogether as irrelevant? Or, why not refuse the privilege or the position of superior tolerate-er of the tolerated?

Rich wanted to insist that lesbians and heterosexual women had something in common, breaking down the hetero/homo divide, which again had potential to reorient us away from hard binaries to something more complex. However, in recognizing only hetero and homo–and especially in holding on so tightly to male vs. female as precisely an antagonism–she stopped short of the radical intervention her piece could have made to thinking systemically about power, inequality, and change.

Putting these two pieces side-by-side, then, produces an interesting look at how far we’ve come–and how far we have yet to go.