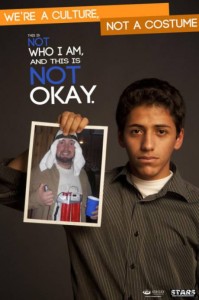

This week, I’ve been provoked into critiquing the casual ease with which people who, by all indications, ought to understand how to avoid stereotyping reproduce the reduction of groups people to the least common stereotype.

Now, I have myself been nailed for this. I wrote in a response paper for my Ethnic Studies 10AC course that “when I think Asian, I don’t think turban” as part of my discussion of the ways Indians get elided. And I was meaning this as a commentary on other people reducing Sikhs to turbans, but that wasn’t clear, and I got a very snarky comment in the margin from my TA. My fault for not being precise. Bad 17 year old me!

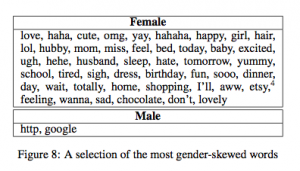

I want to distinguish the objects of my ire here from the Unintentionally Hilarious Figure version of stereotyping, where people had actually found a pattern among groups of people but then just reported it without the necessary commentary or critique:

(I’m pretty sure this got from the Atlantic to me via @anetv but Twitter’s extreme non-searchability precludes verifying. I’ll give her credit anyway.)

Instead, what I’m interested in is the ways that knowledgeable people, generating a name or an image, are using extremely loaded iconography that reproduces stereotypes when they don’t have to. They’re starting from scratch—with the acknowledgement that “scratch” is “the ideas already swirling around in culture around the objects they’re describing”—and yet they deploy these stereotyped ideas, seemingly without sufficient thinking-through.

This first came to my attention when I was forwarded a call for papers: From Veiling to Blogging: Women and Media in the Middle East. This was a goodly while ago now, but it sat there in my inbox until quite recently. The subject is not my area of expertise, so I wasn’t going to submit and should probably have just deleted it. But every time I came to it, I just got mad and tempted to fire off a reply to the listserv about it. I didn’t, because I burn enough bridges on a day-to-day basis without resorting to nuclear tactics, but it was really frustrating.

What was particularly problematic about it was that the people doing the special issue should have known better. The general public discourse around this may well be still about “white people saving brown women from brown men”—Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak specified men doing the saving in the case of sati, but the way some feminists have picked up the veil and run with it makes it an equal opportunity formula—but academics should really know better, because “Can the Subaltern Speak?” is as old as I am.

And indeed the organizers did, in fact, know better, because the actual text of the CFP started out by framing the special issue as a critique of precisely the way that “Middle Eastern women have traditionally been viewed as weak and submissive, passively accepting male authority and leadership rather than seeking to be a leader in their own right” as well as how “women of the Middle East have been portrayed as helpless creatures who are often hidden behind the veil, quietly waiting to be liberated.”

It’s therefore baffling to me why on earth they’d frame the topic as “from veiling to blogging.” Why imply that’s a chronological shift in “women and media in the Middle East” rather than (as they probably intended) in the thinking on women and media in that region? Why redeploy the veil at all, given the enormous risks of re-instantiating the very discourse they’re attempting to dispute?

The second entry in the “wow, you didn’t think that through” file, and the one that solidified my determination to write this blog post, comes from reading the article Minimalist posters explain complex philosophical concepts with basic shapes, which I got from @mikemonello

So there I am, scrolling down, not finding the geometric shapes particularly illuminating—the black and white X for Nihilism, sure, but many of the other Venn diagram-looking ones didn’t strike me as the “surprisingly simple and accessible package” the article’s introduction had promised—when I get to Hedonism and come to a screeching halt.

Really? A pink triangle for Hedonism? What decade is this that we’re still reinforcing the idea that gay sex is about irresponsible pleasure-seeking and gay folks have a worldview in which, as the poster-makers describe Hedonism, “Pleasure is the only intrinsic good. Actions can be evaluated in terms of how much pleasure they produce”? I mean, yes, clearly that’s the world Rick Santorum and other far-right ideologues live in, but the rest of us get that homos are no more or less irresponsible in their pleasure-seeking than anyone else.

If these are people who have enough grasp on philosophy to make posters summarizing it, they should be no strangers to sophisticated thinking. And they should therefore have enough intelligence and sense of the world to think of something considerably less reductive. Like the veiling example, some people may not know better, but these people should.

And I guess that’s the issue. How will the general public know any better if we who do aren’t more careful in how we communicate, to each other (the CFP) and to people in general (the posters)?