In case you’ve been living under a rock, Casey Anthony, accused of killing her two-year-old daughter Caylee, was found not guilty of murder one on July 5 (she was convicted of lying to police). In response, there was widespread outrage, as the court of public opinion had long since convicted her.

You can see how this reaction came about. It was a high-profile trial involving a dead child—that always gets people’s dander up. There also wasn’t a really compelling alternative explanation for how Caylee Anthony died.

And, perhaps most importantly, most people don’t really understand that the American legal system relies on the principle of reasonable doubt. That is, it’s not enough that it seems most likely that the accused did it. In order to prevent convicting the innocent, the system is set up so that, as Wikipedia puts it, “the proposition being presented by the prosecution must be proven to the extent that there could be no ‘reasonable doubt’ in the mind of a ‘reasonable person’ that the defendant is guilty.” That standard wasn’t met, and Casey Anthony walked—whether she did it or not.

But in the midst of all that indignation and sense that justice had not been served was a peculiar pattern. Twitterer MC Thumbtack (pun alert!) hit the nail on the head when s/he said:

@inthefade I haven’t seen this many people outraged over something that has no affect on their lives since OJ’s glove didn’t fit.

Suddenly, it’s 1995 again. I’m sitting in my eighth grade science class watching the O.J. Simpson verdict come down. (No joke, we did this. I think we had a substitute teacher that day.) And, it’s not like I was reading a lot of news when I was twelve, but the reaction in that room indicated that people were mad.

But aside from the outrage factor, I can’t see what on earth Casey Anthony has to do with O.J. Simpson. However, I seem to be the only one.

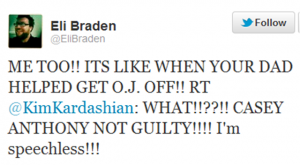

When @KimKardashian tweeted “WHAT!!??!! CASEY ANTHONY NOT GUILTY!!!! I’m speechless!!!” O.J. was the go-to response (only one of them can I find now in its tweet form):

@HaHaWhitePPL So was Nicole Brown Simpson’s family when your dad got OJ off.

Granted, the O.J. link makes a little sense here, as Ms. Kardashian is, in fact—as the tweets note—the daughter of a member of Simpson’s team of lawyers.

But she’s also, as Wikipedia describes her, a “socialite, television personality, model, and actress” who’s “known for a sex tape with her former boyfriend Ray J as well as her E! reality series that she shares with her family, Keeping Up with the Kardashians.” That is, she’s not someone whose opinion on legal matters should be considered terribly important. And yet, people felt compelled to respond and point out the O.J. Simpson parallel.

I wouldn’t have thought anything of it, except that it wasn’t just a couple of responses to a tweet by a “she’s famous for what?” celebrity.

It was Venn diagrams over at GraphJam of “People who have murdered” and “People who can get away with murder” with Simpson and Anthony in the tiny overlapping area.

It was OJ captioned as pulling a Kanye West and saying “Yo Casey, I’m really happy for you. I’mma let you finish . . .” followed by “…but I had the best ridiculous acquittal of all TIME.”

It was a five-picture series of “Totally Looks Like” photos with matching facial expressions between Anthony and Simpson, which must have taken ages to compile.

And it was a deployment of the Bed Intruder Meme. It ran Hide Yo Kids with a picture of Anthony and “Hide Yo Wife” with a picture of Simpson. Later, a version added Lorena Bobbitt and “Hide Yo Husband.”

So why so consistently OJ? Why not other people with similarities to Anthony? There’s a parallel with Scott Peterson, who killed his own kid. And Melissa Huckaby was one of those (relatively rarer) women who kill children—that seems relevant. Everyone was similarly sure Michael Jackson was guilty of child molestation, but he was acquitted, too.

But Casey Anthony hasn’t been compared to any of these people by user-generated humor. It’s all OJ, all the time. And it doesn’t make any sense.

That is, the particularity and consistency of Simpson has to mean something.

And it seems to me that if, as the tenor and sheer volume (quantity and loudness) of the outrage suggests, a mother (allegedly) killing her own child and (apparently) getting away with it is one of the most heinous offenses for our culture, the “the OMG, OJ!” response suggests that a black man (allegedly) killing a white woman and (apparently) getting away with it is right up there alongside it.

So, if the response to Anthony says a lot about gender (OMG, women shouldn’t kill! Mothers inherently have a link to their children, is she a monster?), the consistent linkage to Simpson says a lot about race. Particularly, the ways race in the U.S is to this day freighted with the project of “protecting” white women from black men.

Even when, as in this case, it has absolutely nothing to do with anything.