I have always been perplexed by the insistence that the word “American,” unmodified, should not be used to refer to citizens of the United States.

Certainly, the alternatives are decidedly less than euphonious: U.S. American, United Statesian, and North American (to refer to the commonalities between the U.S. and Canada, which is sure to irritate both Mexico and francophone parts of Canada) are all wildly awkward. But though I’m a sucker for well-named things, that’s only a tiny portion of my problem with it.

I’ve heard the complaint about “American” mostly from or in reference to folks from Latin America, and the argument is that the Americas are a big place and the U.S. doesn’t have a monopoly on the term. As a scholar of unmarked categories like whiteness and masculinity, I know the power that being the default holds, so I understand the impulse from that angle. Refusing the way Anglo folks get to be “American,” full stop, and everyone else is hyphenated makes a lot of sense, particularly in the age of automatic suspicion of any Latino in places like Arizona.

But I’m not sure that the people who contest the way “American” is currently deployed would actually benefit from access to this word.

I get the feeling that most of the world doesn’t have very positive associations with “American.” There’s the “Ugly American” tourist idea. And then, election cycle upon election cycle has appealed to “real America” as white, socially conservative, religious, and inclined to gut all government but super-size the military. And anyone who thinks otherwise is a traitor. “American,” that is, seems to refer to this type of image:

Too fat to walk but still eating junk? Flag-waving and militaristic? Sounds about right. This is the stuff of the ‘Murica meme for a reason–it’s both distinctly “American” and ridiculous to anyone who doesn’t share this particular mindset.

I’d imagine the common attitude, if you did a global poll about the word “American,” is inflected by the logic driving this image. The stance is likely at best mild irritation—and obviously some folks have stoked that into outright hatred to further their own ends (certain terrorist groups and antagonistic nations come to mind).

This then begs the question: Why is anyone who is not hailed by the image of the true, patriotic “American” beating down the door to be associated with this word?

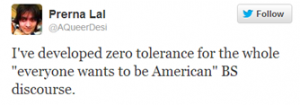

Indeed, the battle for “American” seems to possibly be the mirror image of the ethnocentric American assumption that everyone wants to be American. Seeing this tweet the other day solidified my intent to blog about this issue:

Lots of people surely want access to the economic opportunities and legal protections available in the United States, to the point where they risk their lives to get them—even though ultimately opportunity is highly stratified and not nearly as available as it’s made out to be. In the State of the Union address on February 12, 2013, President Obama discussed how people he met in Burma hoped that U.S.-style justice and rule of law might be coming their way soon. The nation definitely has things to offer that some other places lack.

(I was late in watching the SOTU, but the enhanced version was pretty cool. Though I could have used a bit more Pop-Up Video style trivia to label the people in the audience who were apparently important enough to show on camera. Elizabeth Warren, Eric Holder, and Tammy Duckworth I got, but some help would have been nice.)

But “Americanness” as a cultural identity is not so widely championed. Indeed, the only people I know of who attach a positive valence to it other than not-yet-disillusioned immigrants are “Americans.” That is, it’s popular with a particular subset of people who live in the U.S.—not coincidentally often those demanding cultural and linguistic assimilation of immigrants. Those who’d put flags on their socks but find it offensive to burn one, etc.

Valorizing the state of being “American,” that is, seems to go along with a particular version of patriotism and conservatism and flag-waving and red-state-ness. It’s certainly meaningful to those people, but I remain baffled as to why anyone who didn’t share those demographic and political characteristics wouldn’t just say “actually, we really don’t want that word, we’re going to find something that talks about us in a way we like.”