So, uh, I don’t know if you heard about this, but there’s this Twilight movie thing? With, like, sparkly vampires and stuff? And the latest installment came out recently? People were camping out and everything.

(They didn’t get treated like those other people taking up public space by camping out, though. Apparently, camping out places is a sometimes crime, like cookies are a sometimes food, and, like Occupy Best Buy, waiting to spend money is A-OK!)

But of course, unless you’ve been living under a rock, you have heard of Twilight, and you have been aware of the level of devotion exhibited by fans of the series—exemplified by the camping-out behavior.

Indeed, Twilight fans are routinely the object of ridicule and hatred for the apparent excesses of their love for the books and film series and the personnel involved (actors Robert Pattinson, Kristen Stewart, and Taylor Lautner and author Stephenie Meyer).

For example, when looking for readily available internet commentary on the difference between OWS and Twilight for the aside above, I found a Facebook status message suggesting that the poster was going to “try setting up occupy wall street signs at my local movie theater in hopes that the police will beat and arrest all the twilight nuts camping out,” which is, perhaps regrettably, fairly typical.

Before I go on, full disclosure: I haven’t seen or read Twilight. My exposure to the franchise has consisted of news reports and teaching Buffy vs. Edward every semester (Sometimes twice if I guest lecture. I’ve also been known to show it at parties). I have a group of students making a video about Twilight this semester, though, so perhaps I will soon be educated.

Nevertheless, by means of this indirect consumption of Twilight I have gathered that there’s a lot to critique about the way the franchise frames gender, heterosexual romance, and sexual activity. It is apparent that the text has a lot of problems, but from what I can tell it’s not markedly worse in this respect than other popular teen romances—or, indeed, much of the rest of media.

Okay, so Twilight fans are imagined as hysterical, weeping, teenage, female masses, and this deserves analysis all on its own. That is, though this fits into longstanding traditions identified by Joli Jensen in her now-classic 1992 piece “Fandom as Pathology: The Consequences of Characterization,” the usual story is that stereotyping fans is a thing of the past, as I explained in “Fans Turn to Bomb Threats”: Journalists Turn to Stereotypes, so when these same old narratives crop up again we should take that seriously.

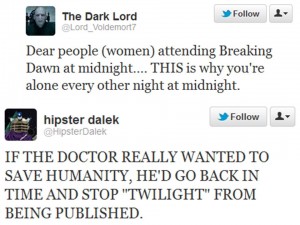

What I find really interesting, however, is not that this happens in general, but something much more particular, something I felt compelled to write about after being retweeted two things:

I have, for a while, been intrigued by the times when fans go around hating other fans, starting with some trends that emerged in my MA Thesis (which apparently has a Google Books entry! Pardon the excessive alliteration. It seemed like a good idea 5 years ago when I named the thing).

But when I got two separate Twilight-disparaging tweets, from two different people, encompassing two other fandoms in the scifi/fantasy speculative fiction spectrum, it seemed like time to take it on.

So, what do these tweets tell us about the cultural meaning of Twilight? People who would attend Breaking Dawn at midnight are women, and they are alone “every other night at midnight”—because they have no family, or no friends, or (most likely given the trope) can’t get a boyfriend. Moreover, Twilight is a scourge on humanity from which we should be saved.

But again, this is standard enough in making sense of things beloved by teenage girls in general and Twilight in particular. What’s really interesting is who we learn it from, and how.

Here we have the humorous Twitter accounts created for a Harry Potter character and a Dr. Who character, the deployment of which involves imagining what these characters might say about current events and writing the tweets they might write. In some sense, this involves inhabiting or becoming the character, if only temporarily. It definitely involves having extensive knowledge of the object of fandom, to conjure the voice of the character accurately.

It is, then, a practice that requires fandom, both in the execution and in the inclination to do such a thing in the first place. Moreover, Harry Potter and Dr. Who are themselves objects whose fans are often subjected to ridicule as losers under the same set of stereotypes about who fans are that they’re deploying against Twilight.

That’s pretty strange. The same people who would surely dispute that Harry Potter and Dr. Who fans are excessively emotional, inappropriately sexual losers are fully willing to not only accept but actively promote the idea that Twilight fans are exactly that.

What this suggests, then, is that not only are anti-fan stereotypes alive and well, but that the very people who are ridiculed by them are complicit in their reproduction. They just think that they apply to someone else.