On May 22, Amazon announced “Kindle Worlds,” a New Publishing Model for Authors Inspired to Write Fan Fiction, and my corner of the fan-studies internet exploded. Reading (and having) those conversations and looking at the big picture, I come to two conclusions: economically, it’s a bad deal; culturally, it’s incompatible with my generation’s understanding of what fandom is and how fan fiction works. Since I got to a full-length blog on just point one, that’s what I’ll tackle this week.

But first, an acknowledgement that, as Francesca Coppa noted in an email exchange in which I participated, “sadly, it’s the best offer yet,” since some in the industry “want to monetize vidding and other fanwork on YouTube and take the all of the profits entirely.” By comparison to this, then, Kindle Worlds looks pretty good, an example to say “look, you really have to cut in the fans if you’ve going to do something like this” (Coppa). I think it’s important to both recognize that this is an improvement and articulate what we like about it (which many are doing) and also articulate what about it is still troublesome (which I’m doing) in order to not let that turn into taking whatever we can get.

Coppa’s point above, that some in the industry feel entitled to the entirety of the income from remix uses of its intellectual property, shows why the analytic lens of labor is so vital. On one hand, that is, it shows why we still need the labor theory of value, because the frequent assumption on the part of industry is that all the value comes from the “raw” material of the media that’s used in remix, rather than something being added by the labor the fan puts into it.

The labor theory of value lets us see the work of value extraction in Amazon’s initiative; they see a thing that could have its value extracted but isn’t being

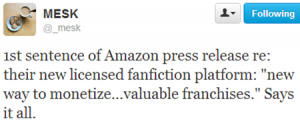

extracted currently, and so they’re extending extraction to it. Hence Melanie E.S. Kohnen’s point:

extracted currently, and so they’re extending extraction to it. Hence Melanie E.S. Kohnen’s point:

(Embrace is always enclosure! The industry’s arms are made of fences!)

We also need a labor framework because what Amazon is offering is, the consensus contends, work for hire (as argued by Livia Penn, Karen Hellekson, and John Scalzi). And it’s work for hire on pretty bad terms.

In the Kindle Worlds framework, writers have no control and have to take what they can get. As Nele Noppe pointed out at the Fanhackers Tumblr,

while fic writers will get some money, they have zero control over how much they might want to charge or how much of a cut they deserve, and no options to negotiate. Amazon can organize its business the way it pleases, of course. But this “you will take what we offer you or nothing” approach may offer a big clue to how Amazon believes the rights of all parties should be balanced out when fic writers and copyright holders try to share income from fanworks.

Penn further points out that, by paying based on net rather than gross profit, fan writers are left open to being billed into oblivion: of a thousand-dollar gross, “a hundred dollars to pay their slush pile department, another a hundred dollars goes to their copyediting department, two hundred dollars to their market research department, another two hundred to their advertising department, and three hundred ninety to the legal department.”

It might seem ridiculous or paranoid to suggest this, but this is well documented in the music industry (Techdirt, Courtney Love at Salon), and Penn gives the example that “the actor who played Darth Vader has NEVER been paid residuals for ‘Return of the Jedi,’ because those come out of… you guessed it, the net profits, and the *fifteenth highest grossing film ever* has NOT made a net profit yet.”

The Amazon Worlds contract, at least as described in the press release, is set up in a way that exploits fan writers’ relative weakness compared to massive companies and the likelihood of their ignorance of these kinds of business practices.

Moreover, Amazon’s offer is a bad deal because publishing this way removes the writer’s control over further use. They (either Amazon or the licensor, it’s unclear) can republish the story itself in anthologies or translations (Noppe, Scalzi, Penn).

The release of all copyright in the contract also seems to suggest that They (whoever They are) can take the ideas in it for other uses; in Penn’s sharp summation, “they are *not* going to pay you more if they take one of your original characters and make them the star of a spin-off web series that then earns them a million billion dollars” (see also Noppe, Scalzi).

(However, this may not be the case; established author Barbra Annino, tapped to write one of the pilot novels, stated that under her contract “if I should create a character within this world, I am free to use that character elsewhere in my own work” and that she understood this to be how the other contracts would work as well.)

The arrangement also quite likely constrains further creativity from its writers, either though prohibiting offering the story for free elsewhere (Noppe) or opening up authors to being sued for copying themselves through writing something too similar later on (Penn).

These are, as both Hellekson and Scalzi (themselves professionals) and legal scholar Rebecca Tushnet point out, worse terms than writers usually get—indeed, as Hellekson puts it, they’re “terms that professional writers would be inclined to reject.”

This is particularly interesting given that (as Coppa reminded me) other literary second-comers didn’t have to give up this much control OR money: Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone didn’t need to license Gone With The Wind; Lo’s Diary reworked Lolita with a 50-50 royalty split with Nabokov’s estate. The difference between “real” writer and fan writer is nontrivial, then, and related again to both not seeing fan work as work that adds value and exploiting (presumed) fan weakness/ignorance.

Both Hellekson and Scalzi gesture toward the benefits of unionization to protect from just such abuses, Hellekson pointing to the Freelancers’ Union and Scalzi to the Writer’s Guild of America as the union for “official media tie-in writers and script writers.”

And then there are a set of non-labor legal issues. One thing that several fan scholars found quite objectionable was the seeming implication that fan fiction required licensing rather than being fair use (Suzanne Scott, Kohnen, Noppe; this is a trouble with licensing generally, see the Brennan Center for Justice’s Will Fair Use Survive?: Free Expression in the Age of Copyright Control [pdf]).

For writing fan fiction, licenses are almost certainly not required, but for selling it they may be, since one of the four factors in Fair Use includes whether the use is commercial. However, commercial uses have sometimes been judged fair (Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone prevailed over Margaret Mitchell’s estate, 2LiveCrew was able to sample Roy Orbison’s Pretty Woman) and noncommercial ones sometimes unfair.

The real issue is that precedent is unclear because cases like fan fiction, where the relationship to the remixed text is not antagonistic, haven’t really been argued before courts. Fans tend not to have the financial wherewithal for such fights; as Henry Jenkins put it in Convergence Culture, “someone who stands to lose their home or their kid’s college fund by going head-to-head with studio attorneys is apt to fold” (p. 131). There’s also the factor of having to fight with the owners of something they love, an affectively and ethically gray area for many fans.

This uncertainty both in the law itself and on the part of fans in knowing the lay of the land (weakness and ignorance again!) works in industry’s favor. They, as Coppa pointed out, know the law quite well and know when things are likely fair use, but they also know they’re likely to get away with insisting on their ownership of fan products.

These questions of labor and compensation and ownership fairness, then, mean that deciding whether publishing with Kindle Worlds is worth doing is complicated and requires having a lot of information and background knowledge that many people don’t. As Scalzi put it, “the thing that can be said for it is that it’s a better deal than you would otherwise get for writing fan fiction, i.e., no deal at all and possibly having to deal with a cranky rightsholder angry that you kids are playing in their yard. Is that enough for you?”

Or Penn:

work for hire is bullshit– well, *unless* you don’t actually deeply care about the stories or characters or other creative work, and just want a paycheck because you have kids to feed. If it’s just a job, then not owning your creative work is fine. (But if that’s the case, you want to make sure you are being compensated fairly, and as I said in point one, “you get nothing but a percentage of the *potential* net from the ebook sales and NOTHING ELSE” is NOT a case of you being compensated fairly.)

Certainly, I think we should take seriously the fact that part of the ease of exploiting this creative labor is that fandom and certain fan practices are still stigmatized. VentureBeat, in its news coverage of the announcement, couldn’t resist referring to fanfiction as “a passionate hobby that earns you ridicule from friends and co-workers.” Fast Company calls fanfic a “parallel universe.” (Obligatory shameless self-promo for my article on fandom and stigma.)

In the end, as I suggested in my SCMS presentation earlier this year, fans’ capacity to consent to such arrangements is uncertain because of vastly unequal power, limited choice, and lack of knowledge. Meaningful consent isn’t impossible, but it does require treading very carefully, and I worry that excitement and the seductions of marketing-speak may render such care difficult to come by.

Stay tuned for Part 2 next week, “The End of Fandom as we know it?”

One Trackback/Pingback

[…] Last week, I talked about the various economic and legal issues involved in Kindle Worlds, like unpaid labor, extraction of value, fair use, and ownership of one’s own creative products. (And that’s what you missed on Glee!) […]