Nothing useful rhymes with arms; I checked.

This week’s post is of course about the revelation of the United States National Security Agency’s PRISM program. But more particularly, it was inspired by two things.

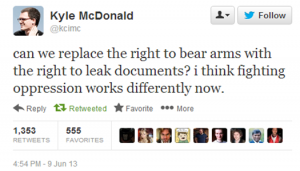

First, a tweet (which I got via @kouredios):

Second, I got a petition from feminist organization UltraViolet via the clicktivism platform Change.org entitled “Hacker Who Helped Expose Steubenville Could Get More Prison Time Than The 2 Convicted Rapists.”

Put alongside the DemandProgress.org/RootsAction.org petition in support of PRISM leaker Edward Snowden, who is apparently “in hiding on the other side of the world because he rightfully fears for his safety — and he says he never expects to see home again,” this all got me thinking.

Both Steubenville hacker Deric Lostutter and Snowden took action to expose wrongdoing, and they are being criminalized for doing so.

The idea that exposing malfeasance is a crime has gotten a great deal of traction in the national security conversation since at least the Bradley Manning/Wikileaks moment. Both The Atlantic and The Guardian characterize the Obama Administration’s crackdown on whistleblowers as unprecedented.

The statement from Director of National Intelligence James Clapper that “The unauthorized disclosure of information about this important and entirely legal program is reprehensible and risks important protections for the security of Americans” certainly participates in this logic of whistleblowing as crime.

A second petition for Lostutter from Credo Action notes that he “was recently targeted by an aggressive FBI raid for his participation in bringing that evidence to light. A dozen agents with weapons confiscated computers belonging to Lostutter, his girlfriend, and his brother, while putting him in handcuffs outside his home,” and certainly the disproportionate and public response looks like a warning to other potential well-intentioned hackers as much as anything.

However, despite this stance on the part of the administration—and members of Congress (Speaker of the House John Boehner called Snowden a traitor, according to RootsAction)—there are important reasons not to see whistleblowing as a crime but more in line with McDonald’s framing above as a vital way to keep the government in line. Certainly one mitigating factor against calling the release of classified information criminal or treacherous is that “the government has been systematically over-classifying information since 9/11” (Rebecca Rosen in The Atlantic)

It’s clear that this is in fact “a secrecy binge,” as Bruce Schneier framed it in The Atlantic, rather than a legitimate act of national security from the fact that “we learn, again and again, that our government regularly classifies things not because they need to be secret, but because their release would be embarrassing.” It seems obvious that exposing things that shouldn’t have been secret shouldn’t be a crime.

However, even if the secrecy serves a purpose other than humiliation-avoidance, there may still be a case to be made for releasing it under the right to know inherent to a democracy. Schneier again: “democracy requires an informed citizenry in order to function properly, and transparency and accountability are essential parts of that.”

Jennifer Granick, Director of Civil Liberties at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, wrote a blog post that called for

public hearings on this scandal so that the American people can find out exactly what our government is doing. Congress should convene something like the Church Commission, which investigated illegal surveillance of civil rights and anti-war groups, to learn how the government conducts secret surveillance and what it does, if anything, to protect the privacy of American citizens.

This is particularly vital in light of what appear to be efforts precisely to avoid oversight. People would, Daniel Solove argues in the Washington Post, “be fine giving up some privacy as long as appropriate controls, limitations, oversight and accountability mechanisms were in place.”

However, “we know that the NSA has many domestic-surveillance and data-mining programs with codenames like Trailblazer, Stellar Wind, and Ragtime — deliberately using different codenames for similar programs to stymie oversight and conceal what’s really going on” (Schneier).

It may well be “entirely legal,” as Clapper says, but we don’t really have any way of knowing that with the information available to us. And even if it is legal, I don’t think that this is what people thought they were signing up for in the post-9/11 surveillance-approval frenzy. As Mike Masnick put it at Techdirt, “those in power keeping screaming “terrorists!” to get Congress to pass these laws, and then everyone’s shocked (shocked!) when the government goes and does what Congress and the courts have specifically allowed.”

However, Masnick goes on, “the ‘good news’ in all of this (if there is any good news) is that if it’s true that everything that was done didn’t actually violate the law, then we just need to fix the laws” if we think this isn’t legitimate. But we cannot do that without knowing how the laws are being interpreted currently.

It is this right to know, vital to democracy, that leads to McDonald’s desire in the above-quoted tweet to frame leaking in terms of the more well-known American ideology about how democracy is preserved, the second amendment. This is actually a very interesting parallel given that both anti-surveillance and pro-gun partisans deploy the Benjamin Franklin quote “they who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.”

The difference between the two positions is in believing in government process. If knowledge is enough, public opinion can rein in government excess or oversteppers can be voted out of office. The pro-gun position seems to foresee the full dystopian scenario requiring force of arms. Even in their distrust, lefties trust the government more.

The absurdity of fighting the world’s most powerful military with civilian-grade weapons, even assault rifles, notwithstanding, I don’t think we’re likely to replace gun rights with leaking rights—cold, dead hands and all that.

But I think the right to leak—which Schneier framed as a duty to leak—is an excellent twenty-first century supplement to push back on government overreach.

Next week, because apparently two-parters are a thing I do now, ends vs. means in PRISM and leaking.

2 Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] Last week, I suggested that the U.S. might benefit from seeking leaking as a useful tool to support democracy in a nontransparent age. […]

[…] Part I and Part II. […]